Two Types of Drifting

"I've heard that there's a kind of bird that doesn't have any legs. So it can't land on nothing. It lives its whole life on the wind."

San Francisco's open secret is that it shelters those who don't quite belong anywhere. But there are two kinds. By day, the streets bustle with people who choose to drift between places. By night, the same streets fill with those who have nothing left but to drift between places. The former reassures me with a semblance of human agency that tantalizes, and the latter threatens me with the raw truth of an unforgiving jungle stripped bare.

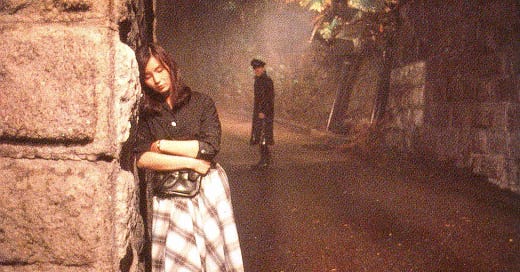

You notice the night drifters most easily in February, the rare time around the year when San Francisco decides to indulge in rain. Like a prisoner granted reprieve from a year-long restraint, the rain hesitates to go back, its continuous kisses cracking open the earth, where shades of green—fresh, old, deep, light—gush out, their boundaries dissolving in the misty air. However, as if dreading the punishment from violating an unspoken curfew, everyone unanimously retreats to their own enclaves before it even gets dark—Neighbors hurriedly draw their curtains, cars huddle under covers, and birds feign sleep.

The endless rain dilutes even the strongest bonds.

That’s when the entire city gives its way to the night drifters. In the emptiness of night, their silhouettes emerge ever more clearly in assorted postures. Some push broken shopping carts, others haul sacks over their shoulders, and a few march forward, wrapped in tattered blankets. They pass by my window—silent, screaming, limping, pacing back and forth, or scanning their surroundings.

They are people, yet at times they resemble anything but, depending on the temperature, the court rulings or the reach of essential services. Year-round, they drift like cottonwood seeds, swept away by the whims of enforcement officers. On a cold, rainy day, they hop on and off buses like community cats seeking refuge in their mobile sanctuaries, waiting for the sun, seemingly believing a nap under its glow could revive them. Yet, most of the time, they silently endure like shade-tolerant plants in damp, dark places—under the Bay Bridge, behind the bushes of Golden Gate Park, in the crevices of Mission District alleyways, in the most resource-savvy movements of vulnerability—the pushing of syringes with shaky hands, the orange glow flickering against cracked skin, the hazy eyes searching the ground for something unseen.

I think of these night drifters whenever I move. I moved more than 20 times in my 20s, sometimes because I had to, more often because I wanted to.

These migrations have finely attuned my senses to credit scores and age buckets, to moments of being let in and moments of being left out, to first times and last times, to what kind of door will close forever, to what kind of person will never see me again, whether someone somewhere wants to leave me better or worse than they found me. I've also mastered the art of not showing up for endings—endings of things I cherished: the end credits, the departing trains, the last shots, the final days. If I don’t participate in its end, then it never ends for me—it is always beginning, always ongoing.

I've heard that there's a kind of bird that doesn't have any legs. So it can't land on nothing. It lives its whole life on the wind. When it gets tired, it just spreads its wings and sleeps on the wind. If it ever does land, even but one time... so it dies."

It is in the midst of this drifting existence, I remember a distinct figure I saw on a February night.

I was working at my desk by the window when I noticed a figure pulling a tattered cart through the dim lamplight on the pavement outside. He lifted his head, looking toward the only source of light — my room — but didn't stop walking. Under his messy hair, I saw the eyes of a young man, which met mine for less than a second: The intense glare in his eyes pierced through the misty night, striking me with a painful clarity, an unbearably strong yearning that made me flinch a little.

I saw this kind of young gaze before I moved to San Francisco. During the long winter of the Covid lockdown, I was living alone in U-District in Seattle as a broke graduate student without any source of income or a driver’s license, though, technically I had a roommate, but she was perpetually at her boyfriend’s place, whom she had found on the dating app everyone despises six months into quarantine and successfully convinced herself to fall in love with. Back then, my weekly grocery run to the Trader Joe’s a few blocks away became one of my few excuses for inmate yard time. Treating each step out of my apartment door as a ceremonious journey, I took the time to savor every detail around me.

It was then I noticed the tent nestled in the indented corner of the exterior wall next to Trader Joe’s. On a deserted street perpetually shrouded in misty drizzle, the crumpled blue fabric of the tent wove into the gray concrete on its two sides, making me feel as though I were walking through a poorly photoshopped dreamcore screenshot. Yet, its persistent stance became a reassuring sight of companionship over time. I peered into the tent a few times, trying my best to hide my attempt, like a child sneaking a peek at a forbidden site, both curious and anxious for the scene awaiting me.

To my surprise, I saw piles and piles of paperback books huddling together, forming an additional layer of enclosure that successfully shielded the tent’s inhabitant. I caught the names of a few trending and classic fantasy series—Tolkien, Martin, Rowling—before my lingering gaze became too shameful to sustain. Though I fled, the scene took me back to my childhood days, when, without a smartphone or wifi, I would always carry a few books with me. They were my shield against the awkward silences of playground politics, my companions during lunch breaks spent alone on the bench when other kids at the dining hall brandished sticks at me until I ran away.

I imagined the kind of person who would carve out a niche fortress of books like that among the various encampment styles in American cities I was beginning to acquaint myself with, like countercultural scenes from third-rate post-punk MVs. There was no such scene on the streets of China, after all. If "being homeless" is a lifestyle that varies by region, I wondered whether this person would have fared better in the small town of my undergraduate college in western Massachusetts compared to the Trader Joe's corner in Seattle.

Back in undergrad, I often ran into a man named George in his 50s at our school library open to all. He was always reading a book or browsing on the public computer. George was among the last to leave, lingering until the closing time when the front desk staff came to kick us out. I recognized him because he slept at the homeless shelter where I volunteered. He told me his family was in Cape Verde, in West Africa. His story is one of a shattered American dream echoing that of many other ambitious chasers. He came here for college in the 80s, only to be ensnared by the plot twists of a foreign land—lost jobs, mounting debts, a health crisis and broken relationships, one thing after another, all of a sudden, nothing was left. Sometimes, when I raced from the library back to my dorm in the freezing wind chills of New England, I imagined George slowly making his way back to the shelter. How would he defend himself against the long nights? Did he ever have anyone to share his thoughts on his readings with? I quickly cut my stray thoughts short—I realized I wasn’t in a position to imagine. If anything, I tend to imagine too much for anyone’s good.

When I got back home from Trader Joe’s that day, I texted my friends about the corner, asking if I should approach the person camping there and offer a small gift, just to say hi. I was nervous and scared. I've always been the kind of woman who avoids eye contact when walking alone, who calls an Uber instead of taking the ten-minute walk home after sunset, so long as the cost fits within my monthly budget. I'd brush it off, saying I didn't want to brave the cold, when my tall male friends innocently suggested I could just walk. I didn’t want to ruin anyone’s mood by recounting the time I was hurled racial slurs and almost run over by an anti-Asian stalker driver in broad daylight, or the time I was knocked down from behind, assaulted, and had my favorite blouse torn. I’ve learned to not to be that character in a cringe comedy who can't grasp social cues and ends up oversharing, only to find herself playing her own supportive audience by forcing awkward laughs to fill the uncomfortable silences.

That said, with my friends' step-by-step remote emotional support online, I finally bought a bunch of bananas from Trader Joe’s. I bent my back, handed them to the unknown shadow, took a deep breath, and spoke in a voice like a nature photographer coaxing a critter out of its cave, “Excuse me?”

I waited for a few seconds that felt like an entire quarantine lockdown to see a face cautiously pop out from behind the fortress—it was the face a young guy, no more than early 20s, with tousled blonde hair framing a face so fresh it could have graced the cover of a hipster band's album. His blue eyes met mine, locking onto me with a silent yet expressively clear gaze that could sting like a bee. I felt a fleeting, sharp pain, soon diluted by the stink in the air.

I asked, “Would you like some bananas?” He replied flatly, “Sure, thank you.” I put the bananas down and fled the scene.

When I got back home, I downloaded an app called Samaritan that claims to put a face to the homeless scene in Seattle by documenting people’s stories. With the frenzy of a stalker trying to dox her anonymous mutual online, I searched through the catalog, hoping to discovering something about this guy. But I didn’t see anything remotely similar. I realized I didn’t even know his name.

His tent remained there through most of the winter. Then one day in spring, I saw him again at a traffic intersection on my way home after getting my first vaccine shot. He didn’t notice me. He was dully pushing forward a shopping cart filled with all his belongings. There were no books in the pile this time. He wore a stern frown, as if displeased with something fundamental about his world, a realm no one else could penetrate.

That was the last time I saw him. I never discovered where his books went before he disappeared.

A year later, I left, too.

I love the tenderness and the peek into the homelessness. I never gave them much thought, here in Germany they are far and few, and usually by choice. Your piece evoke the feeling I have with some people that I had a brush of encounter with, and never to meet again.

A beautiful piece. First: well seen. Second, well written. A round of applause.